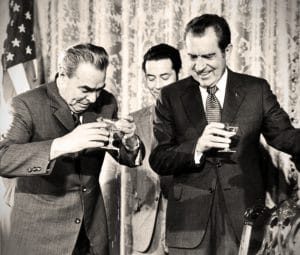

The history of the cocktail is indelibly entwined with modern politics

It may not be immediately obvious, but politics and cocktails have an affinity to rival gin and vermouth.

J-S Dupuis, bar manager at Boulevard Kitchen & Oyster Bar agrees. “The history of spirits and politics — they’ve always gone hand in hand.”

He should know. His dad was mayor of the Quebec town where Dupuis grew up, and even ran for parliament back in the day. That’s left him with a pretty good idea of why politics drives people to drink. “Politics is a very passionate subject. People are passionate about what they believe, and they take it seriously,” he says, adding, “When you’re dealing with politics, you need as much alcohol as you can get.”

When you’re dealing with politics, you need as much alcohol as you can get.

If nothing else, spirits can dull the pain of what seems like one endlessly bitter election campaign after another, from Canada’s 2015 federal election to last year’s acrimonious U.S. presidential vote. Next up: British Columbia’s turn at the polls this spring.

Politics have inspired many a classic cocktail aside from the original “bittered sling,” which we know by its more modern name, the Old Fashioned (whisky, sugar, bitters).

“The Manhattan was a political cocktail,” notes Dupuis. “It was invented for someone who was running for mayor of New York. He didn’t win, but everyone remembers the drink.” In fact, each of New York’s five boroughs had a similar cocktail, including the Bronx (gin, sweet vermouth, dry vermouth, orange juice) and the Queens (the same ingredients, but with pineapple juice instead of orange). Then there’s the Ward 8 (rye whisky, lemon, orange, grenadine, soda), created in 1898 to celebrate an election victory in Boston.

Forgotten now, but potent in the 1920s and ’30s, were the Communist (gin, orange juice, cherry brandy, lemon) and the Liberal (high-proof bourbon, Italian vermouth, amaro, orange bitters). And in the 1940s, there was the non-partisan Black Russian (vodka, coffee liqueur), created for a U.S. ambassador famous for throwing soirées that attracted representatives of all political stripes.

There is a U.S. Senator cocktail, a concoction of many liqueurs that dates back to 1889, as well as El Presidente, named for 1920s Cuban president Gerardo Machado (rum, curaçao, dry vermouth, grenadine). Many world leaders, however, preferred the classic Martini, including Franklin Roosevelt, who not only repealed Prohibition, he hosted a daily White House “Martini Hour.”

And, of course, alcohol itself has frequently been at the heart of political battles, most notably with Prohibition, but most often when taxes were involved (hence the Income Tax Cocktail — basically a Bronx with bitters).

In the 17th century, for instance, the Scottish parliament’s decision to tax whisky played into the English strategy to destroy the power of the clans. A century later, the fledging U.S. government issued its first tax on a domestic product — namely spirits — and inspired its first revolt: the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791 to 1794. “It’s crazy. You don’t learn that in school,” Dupuis says.

Whether in a cocktail or straight up, alcohol has accompanied many of history’s most important political moments — battles won, accords signed, losses reluctantly accepted. Dupuis says he’s with Napoleon on this one: “Champagne! In victory, one deserves it, in defeat, one needs it.”

Go ahead: top up your glass and fortify yourself for the ballot box.

CUBA LIBRE: The former Canadian ambassador to Cuba was accustomed to the country’s leader knocking on the doors of the residence. Lengthy conversations about Canadian politics would take place, eased along by the hearty consumption of Fidel Castro’s favourite cocktail: the Gin & Tonic.

ELECTION ELIXIR: The first definition of a cocktail as an alcoholic drink first appeared in 1806 in the New York publication The Balance and Columbian Repository, where a “cock-tail” was described as, “vulgarly called bittered sling, and is supposed to be an excellent electioneering potion, in as much as it renders the heart stout and bold, at the same time that it fuddles the head.”

—by Joanne Sasvari