It can take years before brown spirits get to market. Here’s how B.C. distilleries keep their businesses liquid in the meantime

Imagine you make widgets: finely crafted, artisan widgets. Customers pay more for vintage widgets, so there are laws around how old they have to be as well as their quality. You spend a couple of years building your factory with expensive, traditional widget-making equipment. You hire workers, pay for raw materials, power and utilities, and finally fill a warehouse with a bunch of bulky, heavy containers, then wait a few years before you can sell any of your exquisite stock at a premium price. In the meantime, you absorb labour and storage costs to maintain your inventory, which you lose a mysterious chunk of every year as some widgets slip through the cracks and just disappear into thin air.

Crazy business model, right? Yet it’s a parable for the artisan distilling industry. “When I went to the bank [for a loan]… the answer was, ‘That’s an interesting concept,’” says Grant Stevely, of the

South Okanagan Dubh Glas distillery. “And they literally laughed. I get it: asking to borrow some money and to pay you back in three to five years doesn’t even sound like a business.”

While making barrel-aged spirits like whisky is the dream for many distillers, the reality is keeping a business running for three years (the minimum legal amount of time it has to spend in a barrel to be named Canadian whisky) or longer. Campbell River’s Shelter Point, for example, waited five years to release its first whisky. So the steady pour of new B.C. gins, like Dubh Glas’s Noteworthy, has something to do with the spirit’s global renaissance, but much to do with the fact that clear gin can be bottled and sold almost as fast as it can be produced, no aging required. Small-batch vodka, so-called “white whisky” (a.k.a. moonshine, white dog, virgin spirit), liqueurs and even cocktail bitters can feed both customers and the bottom line while spirits are aging in the barrel.

“It’s very expensive to make whisky,” says Tyler Dyck, CEO of Okanagan Spirits in Vernon, and president of the Craft Distillers Guild of B.C. “It’s a lot of economic input, a lot of time and operations.” Already a decade into whisky making, Okanagan Spirits is now producing four to five barrels a week. “If you’re not making it now, in five years time, you’ll wish you had been,” says Dyck, who finds people are “blown away” when he explains the aging equation. “They think you can just snap your fingers and make more of it.”

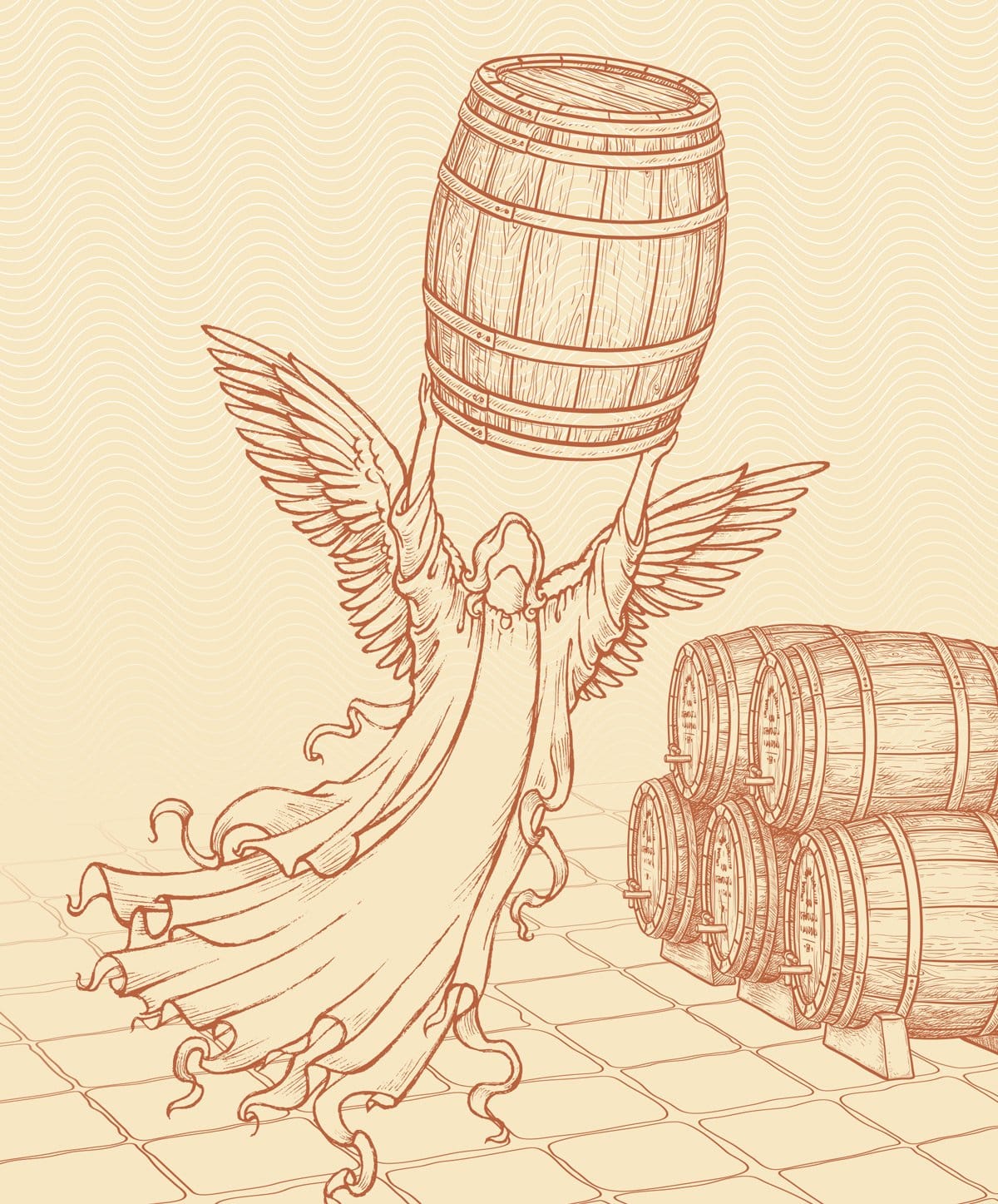

That mysterious loss of your widgets over the years is a real thing, romantically called

the “Angel’s Share”: evaporation from the barrel concentrates flavours — and price, as distillers compensate for their losses.

Temperate climates like Scotland, Vancouver or the Island might lose two to four per cent volume a year. In the Okanagan, “We’re very similar to India: We’re looking at up to 10 per cent loss annually,” says Stevely, who deliberately chose his location after tasting award-winning warm-climate whiskies. Do the math: that could be 50 per cent less volume after five years. He speculates that he’ll have to sell his whisky — planned for 2019 single-barrel, cask-strength releases — for $80 to $100 a bottle.

Temperate climates like Scotland, Vancouver or the Island might lose two to four per cent volume a year. In the Okanagan, “We’re very similar to India: We’re looking at up to 10 per cent loss annually,” says Stevely, who deliberately chose his location after tasting award-winning warm-climate whiskies. Do the math: that could be 50 per cent less volume after five years. He speculates that he’ll have to sell his whisky — planned for 2019 single-barrel, cask-strength releases — for $80 to $100 a bottle.

Like other enterprising local distillers such as Odd Society, DeVine and Urban Distillery, Stevely is selling whisky “futures”: prepaid batches of 30 litres or more that can be yours for the bottling when fully aged in a few years’ time. The advance revenue helps a distillery cover costs and creates word-of-mouth marketing through loyal super-customers. At the new Victoria Caledonian Brewery & Distillery, not only can you work with master distiller Mike Nicolson to customize your batch of single malt (from five new-make spirit options and 10 different casks), you can become an actual investor in the distillery.

President Graeme Macaloney travelled across Canada to bring his vision of world-class B.C. single malt to whisky aficionados and clubs. He is thrilled with the response: “Two-hundred-and-eighty Canadians have already put their hard-earned money into it.”

Futures and shares are two positive factors in the complex equation of barrel economics.

—by Charlene Rooke