Why did BC LCLB agents seize an estimated $150,000 in whisky? And could it happen to your favourite tipple, too?

It was a scene that might have been straight out of Prohibition—were this not 2018.

On the morning of January 19, 2018, plainclothes teams of B.C. Liquor Control and Licensing Branch agents descended upon two licensed establishments in Vancouver and Nanaimo: Fets Whisky Kitchen and The Grand Hotel. Later that day, in Victoria, they visited The Union Club and Little Jumbo Cocktail Bar. What were they after? Illicit booze, grey market goods being sold as the real thing, or maybe something even more heinous?

None of the above, as it turns out. The agents (accompanied by armed police) methodically seized every bottle they could find of Scotch Malt Whisky Society product. Each bottle was duly noted and removed in a rented van. In Vancouver the agents produced no warrant, but said the 242 bottles in question—worth at least $40,000 and as much as $150,000—were being seized as evidence in an ongoing investigation.

The problem, it appears, was that the SMWS bottles had not been purchased through “proper” channels, i.e. the B.C. Liquor Distribution Branch, at least not directly. All of the bottles seized had been procured through private liquor stores, either Legacy Liquor Store in Vancouver or The Strathcona in Victoria, which are the SMWS’ partner stores and exclusive retailers in B.C. The whisky was still taxed at both wholesale and retail levels, but technically purchased illegally, according to the B.C. Liquor Control Act.

Many B.C. licensees turn to the private system when products are not available through regular channels.

Eventually, the licensees were given a 30-day deadline to furnish their proofs of purchase. At press time the investigation remains ongoing, hearings have not yet been scheduled, and LCLB has not elaborated on their action, other than to suggest that it was complaint driven. The branch says it’s not at liberty to disclose the complainant, and never does.

The possible ramifications for the affected licensees are serious. They range from fines up to $75,000 per deemed infraction to 12 months’ jail time or outright loss of licence.

To say that the targeted licensees were surprised would be an understatement. No prior warning or notice of infraction was served in any instance.

So why would a licensee risk all this just to stock their shelves with products from private retailers? Within the industry, it’s well known: Many B.C. licensees turn to the private system when products are not available through regular channels, whether due to lack of selection or challenges with a system that doesn’t always meet their needs. Licensees are reluctant to speak out for fear of reprisal, but anecdotal complaints abound—about lost orders, incorrect shipments, slow delivery times, or orders that just simply vanish.

Among the products that are not available through the LDB are the SMWS whiskies.

SMWS deals only in single barrels, which are numbered and labeled with some of the most tongue-in-cheek tasting notes ever seen—such as “Chestnut purée & new hiking boots” or “Quince jelly baby.”

SMWS is a highly respected organization with some 25,000 members worldwide and has been active in Canada for over five years. The society is, in effect, a worldwide “negociant” for rare whiskies and, perhaps not surprisingly, the largest independent bottler of single malts in the world. SMWS deals only in single barrels, which are numbered and labeled with some of the most tongue-in-cheek tasting notes ever seen—such as “Chestnut purée & new hiking boots” or “Quince jelly baby.” They appeal to whisky aficionados and work with a handful of partner retailers and bars to bring the product to market. Because of the low volumes involved, case lots number in the single digits.

When Rob and Kelly Carpenter explored bringing SMWS Canada to B.C. some six years ago, they were careful to discuss the business model with the LDB to make sure it was all above board. The main spirits buyer gave them their blessing, says Rob Carpenter.

The question most asked at the time of the raids is: Why SMWS and why now?

If there was a problem with SMWS, why did it take LCLB five years to act? And why in this manner?

In a period when the sirens of progress had finally begun to lure BC’s archaic liquor culture into the 21st century, such an aggressive response seems curious, especially given the amount of other specialty products well beyond SMWS that adorn local licensee shelves.

Changes to how and where licensees might more easily purchase specialty and hard-to-find items were up for discussion during the Liquor Policy Review stakeholder hearings process that preceded the 2016 update to Liquor Control and Licensing. But that item has since been redacted from the original list of submissions.

The biggest irony? The tony Union Club is located just down the promenade from the BC Legislature. It is a favoured watering hole of many MLAs, who may well have enjoyed a nip of SMWS whisky now and again. Not any more, though—at least not until somebody comes up with a smart solution and changes the law.

While SMWS Canada co-founder Rob Carpenter is genuinely concerned for the well-being of the bars affected, he’s also philosophical about this being a turning point for more sophisticated tastes.

“For me it’s all about B.C. consumers. They have a choice to make as to whether they speak up about this. If they want to be limited to the choice of (whisky in) government stores, that’s fine. But if they want to go the private route with low volume and spec products, they’ll need to go to the private stores,” Carpenter says.

“We’re just trying to put a product into B.C. that gives whisky consumers a real choice. It’s a shame it can’t be put into bars and restaurants. But it’s really about freedom of choice.”

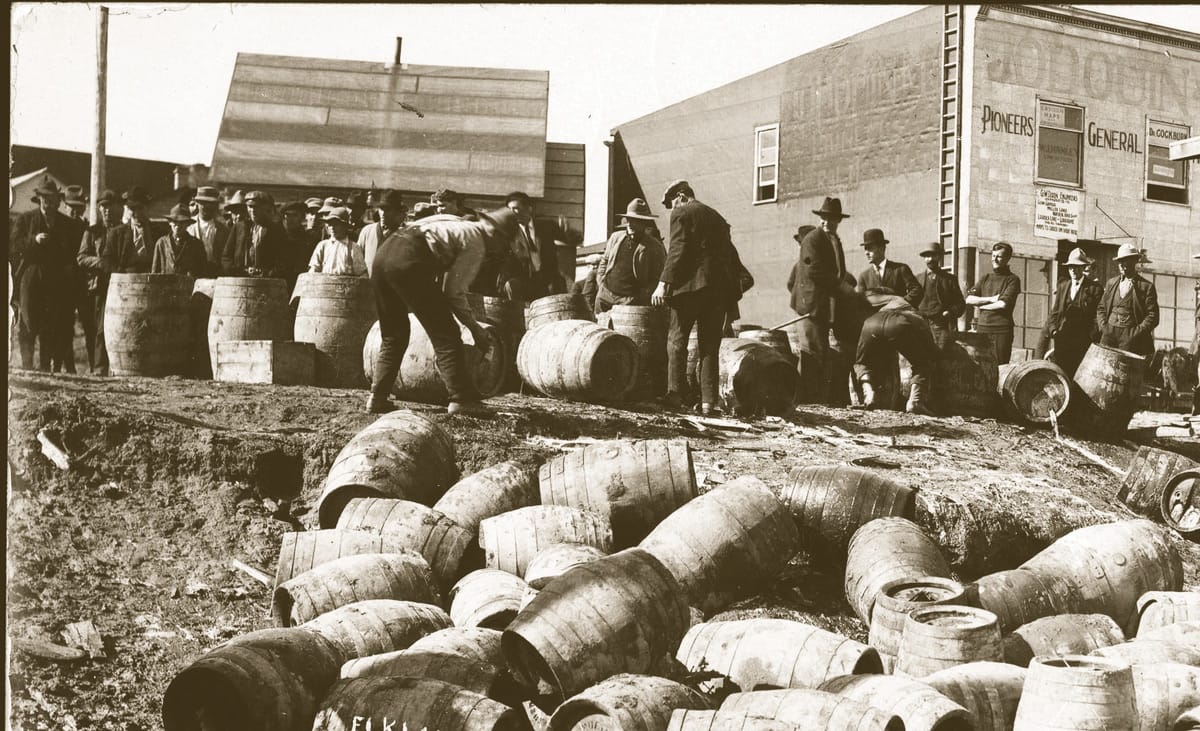

CANADA DRY: The government liquor raids earlier this year have evoked the ghost of Prohibition, which most people consider an American thing (1920 to 1933), without realizing Canada went dry for a number of years, too.

During the First World War, every province except Quebec banned the sale and consumption of beverage alcohol. Prohibition lasted from 1917 to 1921 in B.C., which became the first province to introduce government liquor stores. Then again, because post-war laws were so strict, bootlegging and speakeasies continued here well into the 1950s.

—by Tim Pawsey